Laboratory

Lithium Tests and Techniques

Jan. 4 2021

Geological Sources of Lithium

Pegmatites

Pegmatites are thought to form from: 1) granitic magmas at the final stage of crystallization, or 2) due to partial melting of crustal rocks. In either case, it is a requirement that the source/parent rock composition must contain residual fluids, rich in elements including fluorine, phosphorus, and boron, which are not easily incorporated into melts. These elements, in the presence of high water content, reduce the solidus temperature, viscosity, and density (Bradley and McCauley, 2013). The conditions lead to the relatively rapid formation of megacrystic igneous rocks. Lithium-caesium-tantalum (LCT) pegmatites commonly host Li-bearing ore minerals such as spodumene, petalite, and lepidolite. The LCT pegmatities are usually associated with peraluminous S-type granites. Tin and rubidium are also frequently associated with Li deposits.

Suggested Analytical Methods:

MA270 - Multi Acid ICP-ES/MS, 41 elements

MA370 - Multi Acid ICP-ES, 23 elements

PF370 - Peroxide Fusion ICP-ES, 17 elements

Table 1: Most Common and Economic Lithium-bearing Minerals in Pegmatitic Deposits

| Mineral | Formula | Member | Li (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spodumene | LiAlSi2O6 | Pyroxene | 3.7 |

| Lepidolite | K2(Li)3-4Al8-5Si6-8O20(F,OH)4 | Mica | 1.4 - 3.6 |

| Mica Group | X2Y4-6Z8O20(OH,F)4 | Mica | 1.4 - 3.6 |

| Mica Group | X = K, Na, Ca, Ba, Rb, Cs | Mica | 1.4 - 3.6 |

| Mica Group | Y = Al, Mg, Fe, Mn, Cr, Ti, Li | Mica | 1.4 - 3.6 |

| Mica Group | Z = Al, Si | Mica | 1.4 - 3.6 |

| Petalite | LiAlSi2O10 | Feldspathoid | 1.6 - 2.3 |

| Amblygonite | (Li,Na)Al(PO4)(F,OH) | Amblygonite | 3.4 - 4.7 |

| Triphylite-lithiophilite | Li(Fe,Mn)PO4 | Triphylite | 4.4 |

Hectorite and other clays

Hectorite is a magnesium lithium smectite associated with bentonite. The largest known deposit is in the McDermitt caldera complex on the Nevada/Oregon, USA border, where it occurs in a series of elongate lenses. Hectorite clays can also be found in several other parts of the western United States and Mexico. The mineral is believed to form via hydrothermal alteration of volcaniclastic sedimentary units rich in lithium.

Other Li clay deposits include:

- The Macusani supergene volcanic-hosted deposit in Peru. The mineralization is hosted in altered tuff and contains Li grades up to 0.75% Li2 O, (along with up to 1% U3 O8).

- The Rhyolite Ridge sedimentary deposit in Nevada, USA. The lithium is hosted in searlesite, a sodium-boron-silicate mineral, as well as other clay minerals.

Suggested Analytical Methods:

AQ250-EXT - Extended Pkg, 53 elements, 0.5 g

MA270 - Multi Acid ICP-ES/MS, 41 elements

MA370 - Multi Acid ICP-ES, 23 elements

PF370 - Peroxide Fusion ICP-ES, 17 elements

Brines

Continental

Brines are highly saline solutions often elevated in Li, Mg, Ca, K, Na, SO4 and other elements that commonly form soluble salts. The source of the lithium in continental brines is believed to be due to meteoric groundwater interactions with volcanic rocks. These waters are contained within an enclosed drainage basin and upwell to the surface at the lowest point within the basin. Brine lakes (playa or salar) form in arid climates where evaporation is greater than precipitation. They will precipitate Li as a chloride and concentration will be dependent upon the rate of evaporation relative to freshwater recharge.

The most prolific Li brine resources are located in the high-altitude salars of the northern Atacama desert in Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile. Lithium is also mined from brines in China and Tibet and from subsurface brines in California and Nevada. Grades from producing brines vary greatly from 3000 to 100 mg/L. The mineral is typically mined where the brines are and are pumped to the surface and concentrated by evaporation.

Geothermal

Hot saline solutions driven by geothermal heat circulate through host rocks leaching trace amounts of alkali metals including Li. Extraction of Li from geothermal brines is currently limited, but given the popularity of the metal, production from this source is likely to increase. As an example, brine from the Salton Sea geothermal power plant contains Li grading to 200 pm.

Suggested analytical method:

ICPTV-W - Brine sample analysis for total or dissolved metals

Analytical method and descriptions

Bureau Veritas can support and advise in the selection of appropriate analytical metals for a variety of Li-bearing sample mediums.

Multi-acid digestion (MA270 + MA370)

The sample is digested to complete dryness with an acid solution of H2O-HF-HClO4-HNO3. 50% HCl is added to the residue and heated using a mixing hot block. After cooling, the solutions are made up to volume with dilute HCl in class A volumetric flasks. Samples are run by ICP-ES and ICP-MS to determine analyte concentrations.

Sodium Peroxide Digestion (PF370)

The sample is fused with sodium peroxide in a zirconium crucible. The melt is dissolved in dilute HCl and the solution is analyzed by ICP-ES.

Aqua Regia Digestion (AQ250-EXT)

Prepared sample is digested with a modified Aqua Regia solution of equal parts concentrated HCl, HNO3 and DI H2O for one hour in a heating block or hot water bath. Sample is made up to volume with dilute HCl.

Brine Water Analysis (ICPTV-W)

ICP-ES/MS analysis for high TDS water samples. Analysis would include major and trace elements.

Mineralogy

Lithium may be distributed within in a range of minerals within the one deposit, greatly influencing economic potential and investment decisions. Additionally, purity and knowledge of impurities is of critical importance in lithium when seeking markets.

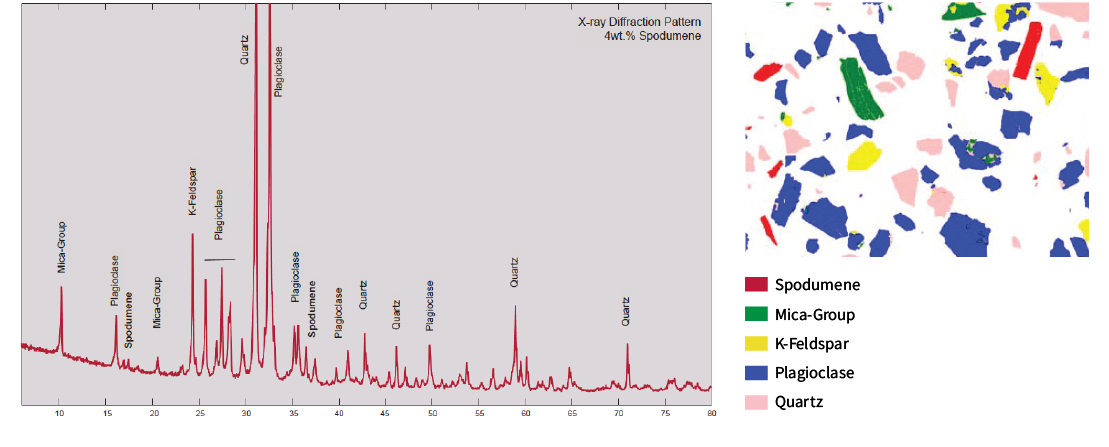

X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

The XRD pattern of a hard rock exploration sample containing 0.24% Li (by chemical assay) is shown below. XRD clearly identifies the primary Li bearing mineral (spodumene) at a concentration of 4 wt.%. However it should be noted that XRD cannot accurately detect elements in solid solutions, such as Li in micas.

Qemscan/MLA

In most cases, automated mineralogy using QEMSCAN/MLA will be able to determine element deportment, however, it is not possible to detect elemental Li due to the limitations of the detector.

Laser Ablation

In Table 2, the deportment of Li was determined by Laser Ablation ICP-MS spot analysis. The Laser Ablation results indicate that up to 30% of the Li content is deported to micas. This was undetectable by QEMSCAN, XRD or chemical assay, and is critical information for determining appropriate metallurgical processes.

Table 2: Laser Ablation ICP-MS Spot Analysis

| Mineral | Li (%) | Cs (ppm) | Rb (ppm) | Ta (ppm) | Al (%) | Fe (%) | K (%) | Si (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spodumene | 4.0 | 0.4 | 1 | 30 | 14.9 | 0.1 | < 0.1 | 29.4 |

| Mica-Group | 1.5 | 1340 | 27600 | 112 | 16.7 | 1.3 | 8.4 | 22.1 |

| K-Feldspar | < 0.1 | 620 | 16300 | < 0.1 | 0.2 | < 0.1 | 13.6 | 29.2 |

| Plagioclase | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 6 | < 0.1 | 11.2 | 17.3 | < 0.1 | 31.2 |

| Quartz | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 46.8 |

Metallurgical Testing and Flow Sheet Development

Brines and evaporites

- Characterization of brines and evaporites (chemical analysis, QXRD, QEMSCAN)

- Crystallisation trials – controlled crystallisation of salts

- Flotation testwork – upgrade of key Li minerals by flotation or reverse flotation

- Beneficiation methods – pilot plant test work

Pegmatites

- Mineralogical characterisation – XRD, QEMSCAN, Laser Ablation ICP-MS

- Comminution testwork

- Head assay and size fraction assays – potential to reject sub-economic fractions based on size

- Gravity beneficiation – separation of impurities based on mineral density

- Flotation beneficiation – upgrade of key Li minerals by flotation or reverse flotation

Lithium Processing from Clays

- Systematic process development studies for upgrading and recovery of lithium from dry lake bed deposits;

- Minerals characterization by Laser Ablation ICP-MS spot analysis and XRD;

- Head chemical assay and size fraction assay;

- Process optimization: roasting; water leaching of calcine and precipitation. The limestone-gypsum roast process is applied to convert lithium in the clay to water soluble lithium sulphate. Impurities from leach solution are removed by precipitation and ion-exchange. High purity lithium carbonate is precipitated by soda ash addition. Lithium recovery of over 80% has been demonstrated.

References

Bradley, Dwight, and McCauley, Andrew, 2013, A preliminary deposit model for lithium-cesium-tantalum (LCT) pegmatites (ver. 1.1, December 2016): U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2013–1008, 7 p.